HTTP — an Application-Level Protocol

Introduction

In Bhutan, when people meet, they usually greet each other with “Is your body well?” In Japan they might bow, depending on the circumstances. In Oman, men often give each other a kiss on the nose after shaking hands. In Cambodia and Thailand, they often join their hands as if praying. All of these are communication protocols, a simple sequence of codes that have meaning and prepare the two parties for a meaningful exchange.

On the Web, we have a very effective application protocol that prepares computers the world over for meaningful exchanges: Hypertext Transfer Protocol, or HTTP. HTTP is an application-level protocol on top of TCP/IP, a communication protocol. HTTP often seems to get forgotten about when teaching web design and development, which is a shame: understanding it will help you to define better user interactions, achieve better site performance and create effective tools for managing information on the Web.

This is the first of a series of articles that aims to teach HTTP basics, and how we can use it more effectively. In this article we will look at where the HTTP cog fits into the Internet machine.

What is a communication protocol?

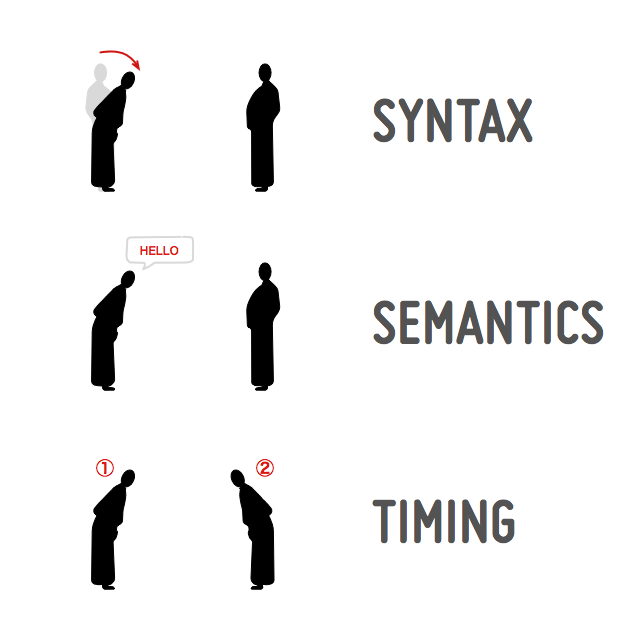

Before looking at the specifics, let’s consider a basic communication scenario. To be able to communicate, two parties (be they software, devices, people, etc.) need:

- Syntax (data format and coding)

- Semantics (control information and error handling)

- Timing (speed matching and sequencing)

When two people meet, they engage using a communication protocol: for example, in Japan, a person will make a specific gesture with the body. One such gesture is a bow, which is the syntax used for the interaction. In Japanese customs, the gesture of the bow (among others) is associated with the semantics of greeting someone. Finally, when one person bows to another person, a sequence of events has been established between the two in a specific timing.

An online communication protocol contains the same elements. The syntax will be the sequence of characters such as keywords we use for writing the protocols. The semantics is the meaning associated with each of these keywords and finally the timing is the order in which two or more entities exchange these keywords.

Where does HTTP fit into the machine?

HTTP itself runs on top of other protocols. When connecting to a web site, for example at www.example.org, the user agent is using the TCP/IP suite of protocols. The TCP/IP model was designed in 1970 with 4 distinct layers:

- Link describes the access to physical media (e.g. using the network card)

- Internet describes the envelope and routing of data — how it is packaged (IP)

- Transport describes the way the data is delivered from the starting point to the final destination (TCP, UDP)

- Application describes the meaning or format of the transferred messages (HTTP)

HTTP is an application protocol that sits above the communication protocol. This is important to keep in mind. Separating the model into independent layers helps to evolve parts of the platform without having to rewrite everything. For example, TCP, a transport protocol, could evolve without having to modify HTTP, the application protocol. In practice, the details become a little bit uglier when we are striving for high performance communication. For the first few HTTP articles we will focus on the separation of layers as defined in the TCP/IP model. HTTP has been defined to communicate information between two pieces of software via HTTP messages. The way we shape and design these messages has consequences on the client (the browser for example), the server (web site) and their intermediaries (the proxy).

Let’s reach a server

Port 80 is the default port for connecting to a Web server. We can try this ourselves using the shell. Open your terminal/command line and try opening a connection to www.opera.com on port 80 using the following command:

telnet www.opera.com 80

You should get an output like so:

Trying 195.189.143.147...

Connected to front.opera.com.

Escape character is '^]'.

Connection closed by foreign host.

We can see that the terminal is trying to communicate with the server located at IP address 195.189.143.147. If we don’t do anything else the server will close the connection by itself. It is entirely possible to use a different port and a different communication protocol, but these are the most common.

Let’s speak a bit of HTTP

Let’s try again to communicate with the server. Enter the following message into your terminal/command line:

telnet www.opera.com 80

Once this is done and the communication is established, type the following HTTP message quickly (before the connection automatically closes), then press enter/return twice:

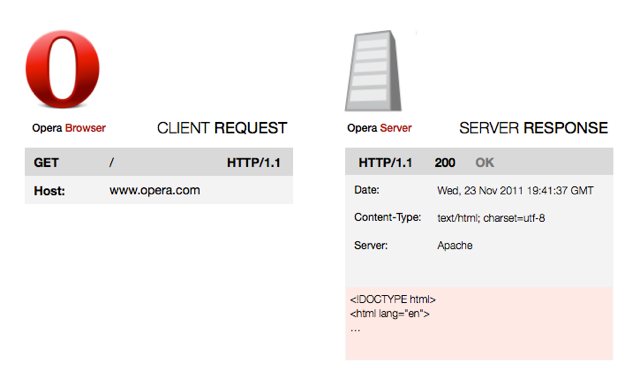

GET / HTTP/1.1

Host: www.opera.com

This message specifies:

GET: That we wish toGETa representation of information./: That the information we want to get at is stored at the root of the site.HTTP/1.1: We are speaking usingHTTPversion 1.1.Host:: I’m trying to reach a specific site.www.opera.com: the name of the site is www.opera.com.

Now it is time for the server to answer. You should see the terminal window fill up with content along these lines:

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Date: Wed, 23 Nov 2011 19:41:37 GMT

Server: Apache

Content-Type: text/html; charset=utf-8

Set-Cookie: language=none; path=/; domain=www.opera.com; expires=Thu, 25-Aug-2011 19:41:38 GMT

Set-Cookie: language=en; path=/; domain=.opera.com; expires=Sat, 20-Nov-2021 19:41:38 GMT

Vary: Accept-Encoding

Transfer-Encoding: chunked

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en">

…

Here the server is saying: “I speak HTTP version 1.1. Your request was successful, so I have responded with the code 200.” The OK string is optional and meant for explaining what this code means to humans — in this case, everything is OK and our message has been accepted. A series of HTTP headers are then sent to describe what the message is, and how it should be understood. Finally, the contents of the page located at the root of the site is included, beginning with <!DOCTYPE html>. The list of HTTP verbs and codes will be explained in the next few articles.

Summary

We just talked HTTP — it is as simple as that! We sent a message (exactly like writing a letter) and we received an answer because our message was understood. Next time we will explore in detail what some of these headers mean and what they can be used for.