HTTP: Let’s GET It On!

Introduction

A few weeks ago, we learnt that HTTP is an application-level protocol. Now it is time to explore how we can use this protocol to communicate between the client and the server.

Getting things on the Web

Remember that the HTTP client (browser) is always initiating the request to the HTTP server. The HTTP protocol gives the client a few tools to express its intention to the server: The URI, the HTTP methods and the HTTP headers.

Give a name to things

URIs are one of the cornerstones of the Web. They solved an important issue that existed on the Internet at large: how to uniquely identify something on the network.

Now, if you ask someone to grab an object and bring it to you, there are not many solutions. The words you use will start to identify the object you need.

- You could ask a friend: “Bring me the book”

- The friend might reply: “OK, but which one?”.

- You: “The book in the other room.”

- Friend (goes to the other room): “Huh? Which one?”

- You (slightly annoyed): “The green one!”

- Friend: “Hey… calm down. There are two green books here!”

You stand up and finally get the book yourself. But all of that could have been a lot simpler. How do we uniquely identify these things we might want to access later on? Memory is one possibility. How do we give instructions to someone to get the right object? Let’s create a system for it:

- Cut pieces of papers or use yellow sticky notes.

- In the room around you or on your table, put the empty notes near or on top of the objects (for example books) you need to access later on.

- On each note, put a unique ID.

- Repeat the process in another room or on another table.

Remember that it is not only for your own usage but it will enable interactions (and obviously avoid your frustrations). I just did it for me. I have written on the pieces of papers, the following identifiers attached to each object.

myRoom.org/table/book/001

myRoom.org/shelf/book/002

otherRoom.org/cup/001

otherRoom.org/flower/001

otherRoom.org/book/001

I think by now you’ve got it. We now have a system of labels for identifying precisely things in a space. On the Web, we are dealing with an information space and the labels identifying this information are URIs.

Access the identified things

In the last article, we learnt to craft an HTTP request on the command line. We used a very minimal construct with the HTTP method GET and one HTTP header: Host.

GET / HTTP/1.1

Host: www.opera.com

The full list of current HTTP methods is: OPTIONS, GET, HEAD, POST, PUT, DELETE, TRACE, CONNECT. Each of them have different roles that we will explore in further articles. GET is by far the most used one. Each time, we enter an HTTP URI in the browser address bar, we send a GET request to a server.

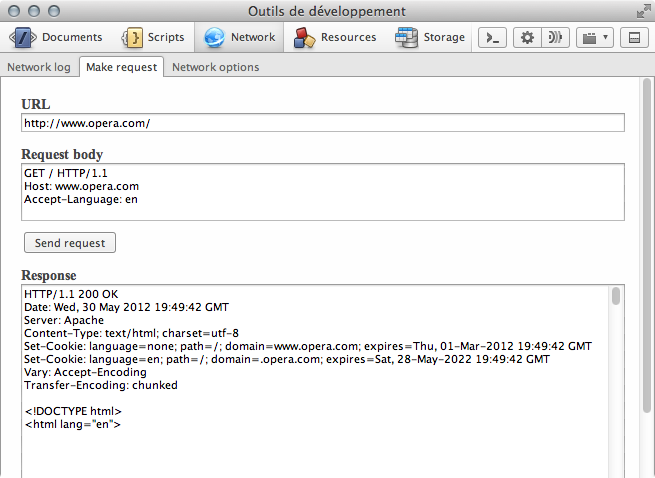

On the Web, a lot more information (HTTP headers) is sent by the client to the server to help with negotiating the HTTP request. The server then will be able to adjust its answer according to these headers. There is a very practical tool in Opera Dragonfly to create custom HTTP requests and inspect the server HTTP response: you can find it under the Network section, in the Make Request tab.

In the Make Request tab, there are three areas:

- URL: The resource identifier (or Web address)

- Request body: What the client will send to the server. (The button “Send request” will actually send the request across the network to the server.)

- Response: The response of the server once the request has been made.

Let’s customize the HTTP request

- Copy

https://www.opera.com/in the URL section - Copy and paste the following HTTP request into the “Request body” section of the network tab. We added the

Accept-Languageheader to the previous minimal HTTP request. - Then hit the “Send request” button.

GET / HTTP/1.1

Host: www.opera.com

Accept-Language: en

The Opera HTTP server will reply with a few HTTP response headers and the markup for the document. You may have to scroll in the window: the response can be long. Notice that the document is in English — not only in terms of written language, but also explicitly specified in the html element’s lang attribute:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en">

Let’s try with French:

GET / HTTP/1.1

Host: www.opera.com

Accept-Language: fr

This time server responds with French specified in the markup and the actual text of the document.

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="fr">

We used exactly the same URI — https://www.opera.com/ — and we received different answers only because we changed the HTTP Accept-Language. Note that the server replied with plenty of headers — giving us in return information on the resource status such as its type, etc. That will allow the client to adjust the processing of the document. You can try it with different languages: ja for Japanese, de for German, etc.

What happens if we request a language that doesn’t exist on the server? Just try it: for example zh for Chinese:

GET / HTTP/1.1

Host: www.opera.com

Accept-Language: zh

You got the English version of the Web site — puzzled? This is part of the design choice of the Web site. The server HTTP response could have been designed in a different way: it could have simply replied “no, we do not have a Chinese version for this address” or “There is no Chinese version for this address, here are the languages we do have available” (with a list of links to specific versions in different languages). But the Opera UX department decided that when the request language was not known, the server would send by default the English version. It is really a question of choice: there is no formal standard here.

It’s why I often teach a bit of HTTP to UX people and front-end developers. HTTP is an application protocol for managing the interactions between a client and a server. As such, understanding how it works will help with designing meaningful interactions when creating a Web site for both humans and machines (bots, API clients, etc).

What you need to remember

- URI: A system for identifying pieces of information on the network.

- HTTP Methods: The protocol currently contains 8 methods for requesting a URI:

OPTIONS,GET,HEAD,POST,PUT,DELETE,TRACE,CONNECT. In this article we focused on the most commonly used one:GET - HTTP Headers: The headers are additional data sent by the user agent to give more context about the transaction going on between the client and the server. Some of them will help the server reply in the most appropriate way.