Barcodes: Connecting the Real-World to the Virtual

Introduction

The world of barcodes is becoming vastly more interesting in recent times, with 2D barcodes allowing us to represent anything from URLs to invoices, which in turn allows us to connect physical images to applications in all kinds of interesting ways. In this article I will look at the history of barcodes, detail what’s available today for creating and reading barcodes, and look at some real-world use cases.

Barcodes: a brief history

Life is truly black and white when you are dealing with barcodes. Those little lines that grace the backs of our books, boxes and just about everything else have become ubiquitous in our society — so much so that they have become symbols of capitalism, namelessness and government control. Some readers have never known a world without barcodes, and for others it may just seem like that, but the barcode is barely in its middle-age crisis. Officially, the first patent for a barcode was awarded in October 1952 for tracking train cars. It was another 14 years before the barcode caught the eyes of manufactures and put into commercial use. Another 15+ years forward to the 1980s, and barcodes were being slapped on just about everything we buy.

A barcode is a combination of thick and thin lines used to represent a series of numbers. For books, these numbers encode an ISBN, which has become so popular it had to be extended from a 10 to a 13 digit number! But a barcode can encode any value, not just ISBNs. The series of lines represents digits, and the thickness and combination of those lines describe which digit is being encoded.

The traditional barcodes you see everyday are sometimes called one-dimensional barcodes. This is because they are scanned, or “read”, in only one direction — horizontally. The vertical height of the barcode makes for easy scanning, but in itself does not add any additional information. The next generation of barcodes is generally referred to as 2D, two-dimensional, barcodes. These new style barcodes get their name from the ability to be read both horizontally and vertically, therefore increasing the density of information that can be encoded in the same amount of space.

2D Barcodes

There have been several types of 2D barcode put out onto the market, but only a few have been implemented and show any real promise in the industry. This article will be demonstrating a 2D barcode called QR code. Much of what is demonstrated here can also be done with other 2D barcodes, including the also-popular Data Matrix barcode. I will be using QR codes, because in my opinion, they are the best solution at the moment. They are more robust and have more promise and adoption than the other variants. The other major barcode type to keep an eye on is PDF417. This standard is being adopted by the airlines industry to encode self-printable boarding passes. A 2D barcode style ticket will be required across the entire airline industry by 2010, so you can be sure that this technology will only expand into other aspects of our daily life as well.

QR Codes

QR codes are the most robust of the current 2D barcode formats. They have wide adoption in Asia and Oceania and are making headway in Europe and the Americas. What makes QR codes so special is that they are capable of encoding non-ASCII characters, along with URLs, telephone numbers, SMS messages and even binary data. With these options and more, it is a natural fit when extending 1D barcodes from a number, to a string of characters.

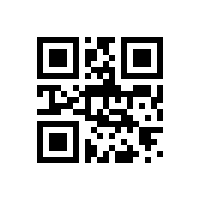

Since you can encode just about any data, you can begin to use it for applications such as inventory control or unique ids for database look-ups, and beyond. Figure 1 is an example of what a QR code looks like.

You can recognize a QR code by the 3 large squares in the corners. These are registration marks — they tell the QR Code reader which side is the top. A good scanner can read a 2D barcode from any direction and rotate it in memory so those registration marks and the rest of the barcode are in the right orientation. The black and white squares in the area between the registration marks are the encoded data (well, it is slightly more complex than that, because there is some error checking and correction added into those squares). This makes the format even more robust and resistant to damage from the elements. With the highest level of encoding and error checking it is possible to damage up to 30% of the barcode and have it still be decoded into its original data.

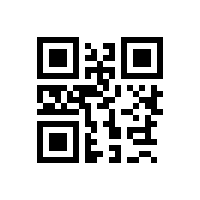

QR codes can also encode more data than other barcode formats, over 4000 ASCII chars. The more data that gets encoded, the larger the barcode grows. Figure 2 is a barcode representing 500 characters.

You can see that the dimensions have grown and there are additional, smaller, registration marks to incorporate the additional information.

Creating QR Codes

The Google charts API allows you to easily create QR codes without having to understand the underlying algorithms. Let’s have a look at how to use it, step by step.

The base URL for creating dynamic charts is http://chart.apis.google.com/chart.

But that’s not enough; this current URL will give you an error. We need to pass some additional information to let Google know the kind of chart we want to create, the dimensions of the image and the data to encode. To do this, we add a ? at the end of the URL followed by name value pairs containing the extra data. Since we are creating QR codes, we first need to pass that value in the URL, like so:

http://chart.apis.google.com/chart?cht=qr

The parameter cht stands for chart type. The value is qr for QR Code, because that is the type of chart we want. Google offers a full range of chart types, all of which are described at The Google Chart API Developer’s Guide.

Next, we want to define the size of the QR Code. To do this we need to pass the chs chart size parameter with the height and width dimensions. The new URL looks like this:

http://chart.apis.google.com/chart?cht=qr&chs=200x200

This URL generates a QR Code, but we still haven’t passed it any data to encode. To do this we pass the last required parameter chl, which stands for chart label. This is a string of the information to be encoded. We are going to use the string My First QR Code, which when URL encoded becomes My%20First%20QR%20Code (all the spaces have been converted to %20). This gives us a final URL of:

http://chart.apis.google.com/chart?cht=qr&chs=200x200&chl=My%20First%20QR%20Code

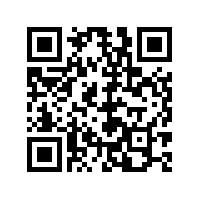

The resulting QR code looks like Figure 3.

Reading 2D barcodes

Creating a 2D barcode is only half the story — the next step is figuring out how to read them. We have recently passed the technical tipping point for the 2D barcode readers. The software needed to decode the barcode algorithm will run on even the slowest of processors with moderately good imagery. What is being described is the everyday camera phone.

There are various free applications for reading the different types of 2D barcodes, and these are just a few:

- Kaywa creates a free QR code reader that works on a variety of devices.

- Nokia software for reading several 2D barcode formats comes pre-installed on newer high-end phones.

- There are also software projects for 2D barcode readers on the iPhone and Android platforms.

Using the Barcode reading software is easy. You simply launch the application, point it at the barcode (see Figure 4) and the information is decoded.

What are 2D barcodes used for?

Previously, traditional barcodes all had to go through some sort of central authority for ISBN registration. You were also required to purchase specialized hardware laser readers to scan these barcodes, making it impractical for everyday personal use. With 2D barcodes any type of data can be encoded independent of a central registry. As the mobile device is becoming more and more ubiquitous and more and more powerful every day, we can use its capabilities in new ways, for new applications. This opens the door to reading 2D barcodes and converting them to a wide assortment of information that the phone can act on.

After plain text, the next example to encode is a URL.

If you decode this barcode you will get the URL http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hello_world in return. Your phone will recognize this as a URL and ask you if you want to launch the web browser and visit the site. For short URLs, you’d wonder why this is useful. For longer URLs it is obviously a time saver, because it is a pain to type a long URL in with T9 on a numeric keypad. Having a barcode makes it much easier to enter and access the data. Another side effect of not having to type URLs, is that you can take a photo of a barcode while wearing mittens. All new Nokia phones ship with a barcode reader and in the sub-zero temperatures of a Helsinki winter, you can bet it is much easier to launch a web browser and check URLs via a 2D barcode than take off your gloves and try to spend 30 seconds typing them in!

Your phone is much more versatile than just accessing URLs. Your desktop web browser knows several different protocols – http, https and mailto to name a few. Your phone, on the other hand, knows about these and some others, namely the tel and sms protocols. In much the same way that you link to an email address with mailto:userexample.com, you can link to a telephone number with tel:123.456.7890. The former will launch your email client so you can send a message, and the latter will launch the dialer on the phone so you can make a call. The protocol sms:123.456.7890 works in a pretty similar fashion. Now you can begin to encode barcodes that act as links to dial out.

This is just the beginning — it is possible to encode more than just URLs and links. You can encode data files as well, such as vCards. This allows people to simply take a photo of your 2D barcode to import all your contact information into their address book (as seen in Figure 7). No more mis-typing or mis-spellings!

It is also possible to encode binary data as well. Imagine the concert poster of the near future (or see Figure 8 to preview it): A large retro 2-color poster with the band name & photo. At the bottom there is a series of 2D barcodes. The first is a link to a calendar file. You follow the link and it adds the concert dates into your phone’s calendar so you don’t forget about it and double book that evening. Another 2D barcode is a 30 second mp3 clip of the band that you can check out to get a preview of the band. The 3rd 2D barcode links you to a site selling tickets to the event. You take a picture of the barcode and it decodes to some long cryptic URL specific to the ticket vendor’s outdated eCommerce system. You launch the browser with the URL and order some tickets for this Friday night. Instead of typing in your credit card number, you simply get the price of the tickets added to next month’s phone bill.

Summary

Exciting stuff huh? These small black and white squares become links from the physical world into the digital world. We can now begin to annotate objects that you can see and touch and continue the conversations online in a world were anyone can contribute to the conversation without also having to be physically next to you.

The biggest hurdles to adoption of 2D barcodes are not technical issues; these are solved. The next phase of their evolution is user interaction. On the web people have learnt that underlined blue text is a link. We need similar conventions for barcodes — where does this barcode lead, is it a URL or an email, or a phone number? There are no de facto standards for interactions — we are learning as we go, testing what works and what doesn’t and mapping that to user expectations. There is much more to be explored beyond the technical achievements of 2D barcodes and that is where the real interesting parts begin.