Release the Beacons!

Norway is the nation that gave the world the paperclip and the cheese slicer, so it’s easy to see that R&D is a national tradition here (it stands for “research and development”, not “reindeer and dogsleds”, although those are nice too).

Today, Opera R&D released a labs build of Opera for Android (APK, 30 MB) with URL beacon detection.

What are URL beacons?

A “beacon” is defined as “a fire or light set up in a high or prominent position as a warning, signal, or celebration”, and this is very much the same in the context of the Physical Web (aka “The Internet of Things”). A beacon is a low-powered chip with its own power source that does one thing: it broadcasts information, using a Bluetooth low energy (BLE) message format like Eddystone, AltBeacon or iBeacon.

These formats compete with each other. The latter two broadcast a Unique Identification Number (UID), so users need an app specific for those beacons, or require Apple’s Passbook to do anything with those UIDs.

Eddystone, named after a famous British lighthouse, simply broadcasts a URL. This simplicity makes these URL beacons especially interesting in the context of the mobile web. (Eddystone actually supports broadcasting UIDs as well. This Opera Labs build currently only supports Eddystone-URL.)

When a user with Bluetooth software comes near a beacon, their device can pick up the URL. And what better way to handle a URL than with a browser?

Labs build

Today’s Labs build is Opera 32 for Android, with additional beacon goodness. Installing it won’t overwrite any existing installations of Opera for Android or Opera Beta. (If you have a previous Labs build of Opera, uninstall that one first.)

To use beacons, accept the dialog shown on first run. Beacons are shown in the “Nearby” panel, which you find on the right of the “Discover” panel. Two swiped to the right and you’re there!.

Here’s a photo taken at our local bus stop. The bus stop is broadcasting a unique URL (other bus stops can broadcast different URLs).

For those who don’t read Norwegian (why not?) it’s telling us that the number 30 to Bygdoy is coming now, the number 30 to the Opera office in Nydalen is coming in 5 minutes, which is lucky, or we’d be late for work again. (Not our fault! We were in the pub last night — checking out their beacons, naturally.)

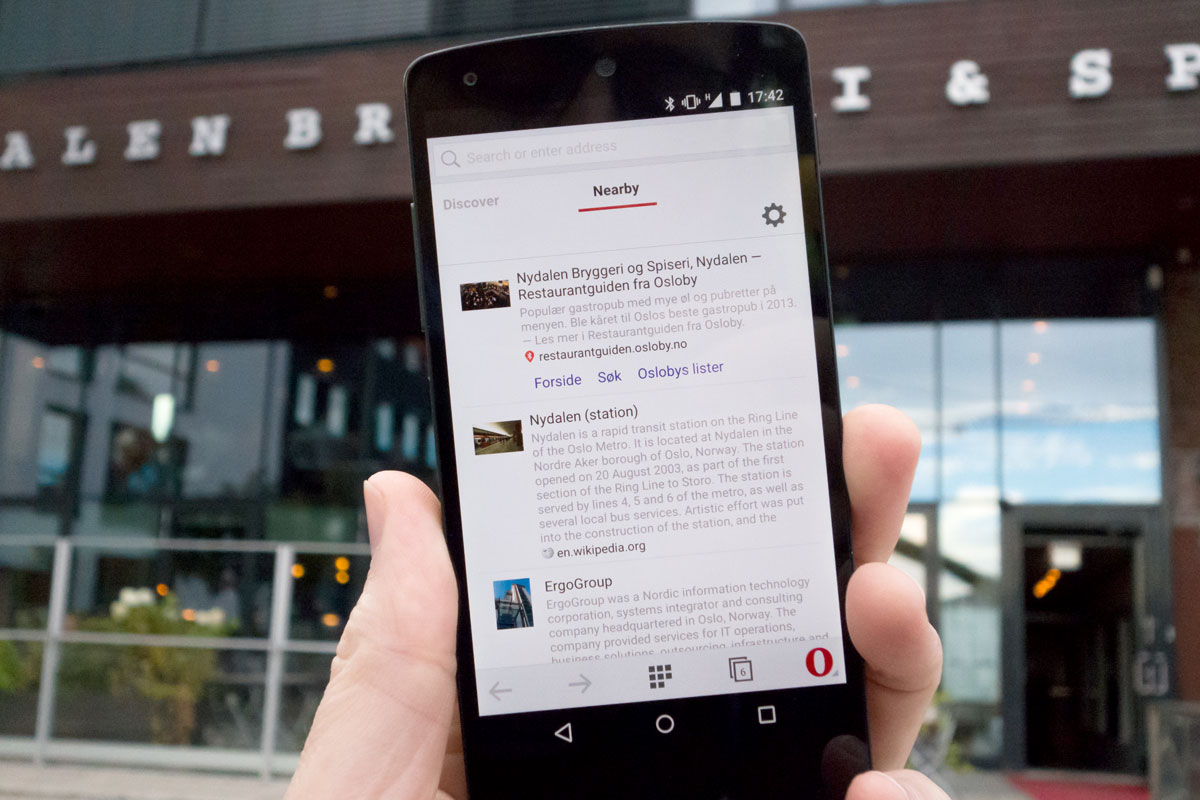

Additionally, as there are few beacons “in the wild” at the moment, this Opera Labs build’s “Nearby” panel shows Wikipedia entries based on geolocation, so that there’s always something shown. This allows for a mix of geotagged “general interest” Wikipedia stuff, and very location-specific info coming from beacons.

Beacons will trigger an Android system notification, so you can easily find out if there’s a new beacon around. Wikipedia results on the other hand do not display a notification.

Security and privacy

Beacon signals are one-way only. They are emitted by the beacon, and picked up by your phone, and nothing is ever sent back to the beacon. This is great for privacy, because it means that the owner of the beacon cannot track anyone who steps within range.

There is, however, a privacy trap here that we could fall into if we’re not careful. Consider the naive beacon-scanning application: it sits in the background of your phone and scans for beacons. Every time it sees a new beacon, it resolves a shortened URL to a real URL. Then it fetches the web page at that location, in order to extract some metadata to show you. The problem here is that the owner of the beacon probably controls the web page. When they see that you request the web page, they know that you’re probably near the beacon. If they own a lot of beacons — maybe it’s an international chain store or a fast-food establishment — they can track your IP address wherever you go.

To better protect you, the beacon scanner in the Opera browser comes with an anonymizing service, which shields you from making direct contact with these web pages. Rather than fetching metadata from the web page directly, the Opera browser sends a request to our server. The server will resolve URLs, fetch and parse pages, and prepare icons, then return just the bits you’re interested in. This results in less data traffic used, fewer CPU cycles spent and most importantly, better privacy (provided, of course, that you trust Opera).

Populating the Nearby list

So maybe you’ve ordered yourself a handful of beacons, and you want to prepare your web pages for beaconization (new technologies require new words). But, how exactly does the “Nearby” screen in the Opera browser transform full web pages into simple list elements? If you want to make your page look good in the “Nearby” screen, you’ve got three choices at the moment — just use one. We recommend plain HTML.

HTML

This is maybe the most straightforward solution. Use the <title> element, the <meta name="description"> element to hold the description (any line breaks will be replicated in the “Nearby” panel) and point <link rel="icon"> tag point to a high-resolution icon. A 144 × 144 PNG will look great.

Open Graph

As an alternative to the approach above, you can use the following Open Graph tags, respectively: <meta name="og:title">, <meta name="og:description"> and <meta name="og:image">.

Schema.org

Finally, you can choose to annotate your HTML with Schema.org microdata. Specifically, we look for the tags <meta itemprop="name">, <meta itemprop="description"> and <meta itemprop="image">.

Example

As an example, the “bus stop” URL has the following markup:

<head>

<meta charset="UTF-8">

<meta name="description" content="

30 til Bygdøy via Bygdøynes om 2 min

56 til Solemskogen om 4 min

30 til Bygdøy via Bygdøynes om 12 min

30 til Nydalen klokka 14:54

56 til Solemskogen klokka 14:58">

<meta http-equiv="refresh" content="30">

<link rel="icon" href="ruter.png">

<title>Gullhaugveien</title>

</head>

The page title of the “Nearby” entry comes from the HTML <title>, the icon from the <link rel="icon"> and the main content from the <meta name="description"> element; line breaks in the content of the tag are reproduced in the Nearby panel. The <body> of the page is irrelevant, so one URL can be used to populate the “Nearby” panel and as a conventional web page.

Hardware support and battery usage

Depending on the Bluetooth hardware in the device, this Labs build can drain the battery. Newer hardware offloads scanning to the Bluetooth chip, and you will not notice any extra battery usage. But older hardware (like the Nexus 5) wakes up the device at specific intervals and will thus drain the battery faster. You can check this from “Nearby” → Settings cogwheel → Debug information. There we show the level of hardware support and estimated battery usage (low, medium, high).

Setting up your own beacons.

It’s easy to buy Eddystone beacons, and to set them up from a computer, using a Bluetooth 4.0 Low Energy dongle. Opera’s Tommy Thorsen wrote a python script to advertise a URL using Eddystone-URL.

Why are beacons a good fit for Opera?

We at Opera R&D really like beacons, especially URL-beacons. As a web browser, URLs are exactly what we’re good at, and new ways to discover more URLs is great news for us. But, what will we do with these URLs? And what can beacons really be used for?

You can divide technologies into two groups: technologies that have a specific use case vs. technologies that can do all sorts of stuff, but we’re not sure what the interesting use cases are. Some of the most revolutionary technologies fall within the latter group. Take the World Wide Web as an example; the technology is really just bits of text that can contain links to other bits of text. But, as people have started using and extending the technology, we’ve taken it to a level which surely no one could have imagined a few years ago. Or, SMS, which is just an afterthought in the GSM specification but, despite (or because of?) its limitations, became hugely popular.

New use cases will come about when the Web Bluetooth API is finished: you can then discover and use Bluetooth smart devices directly from the browser. For instance, here’s a cool Firefox OS demo Flying a drone in your browser with Web Bluetooth.

Can beacons be the next groundbreaking thing? That’s hard to say, but the technology has that potential: like the web and SMS, it provides a simple but versatile service, on top of which developers can improvise and innovate. Linking beacons to the web, via the browser, is a solid step forward, and will hopefully accelerate that innovation.