Installable Web Apps and Add to Home screen

Today, we’ve launched Opera 32 for Android. Along with a host of bug fixes, stability improvements and an updated Chromium engine for maximum compatibility and security, you’ll find some features that are deliberately designed to bridge the gap between native apps and the “mobile web” (or, at least, the web viewed on mobile devices).

(Updated 30 September 2015: today’s update to Opera 32 for Android changes the name selection criteria.)

One of the bigger gaps has been the difference between bookmarking a site and installing an application. We know that, even on desktop, most people don’t use bookmarks. We also know that people love “installing” apps that live on a device’s homescreen, with a crystal-clear icon imploring them to tickle them into life with a tap of the finger.

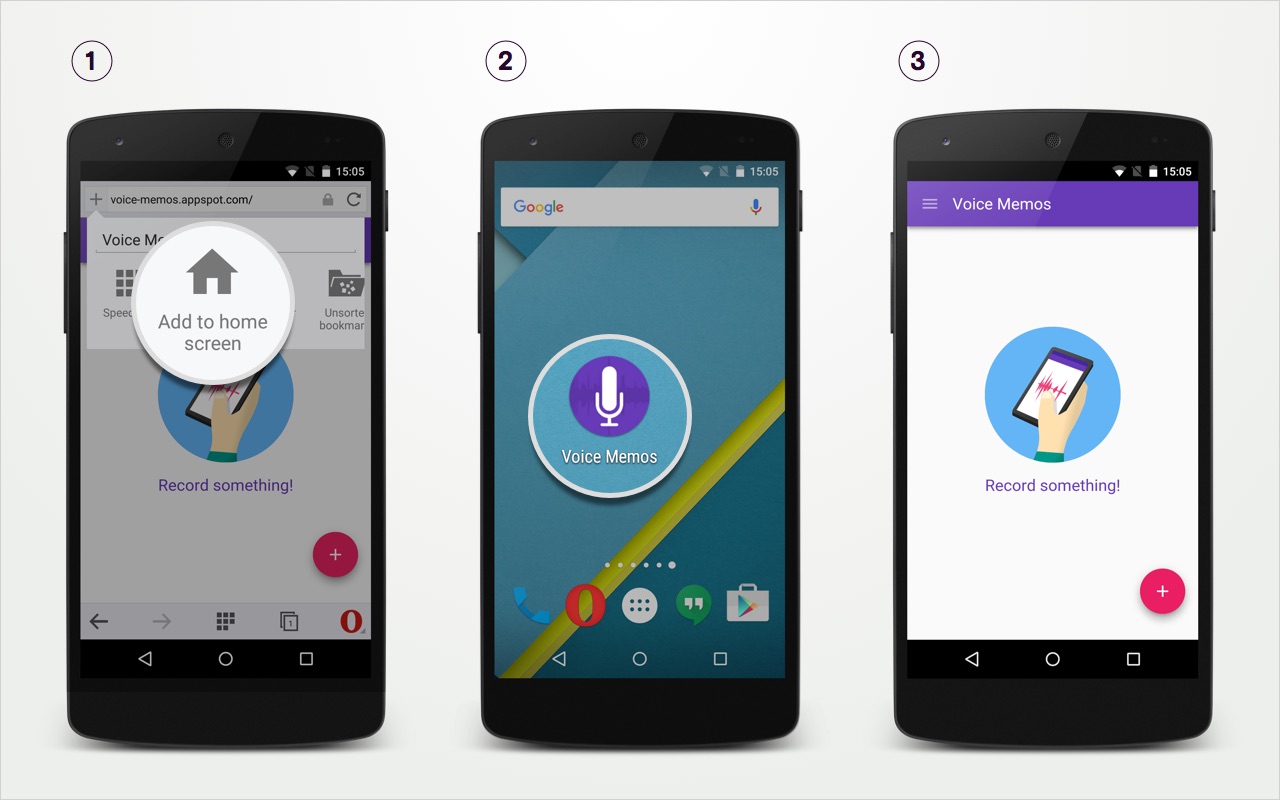

When a user loads a site in Opera 32 for Android, taps the plus sign, and chooses “Add to home screen”, a shortcut to this site is placed on the home screen of her/his device, allowing for direct access and increased visibility.

Through the magic of web standards, site owners can make this even better: by serving the site over HTTPS and providing some metadata in a manifest file a web app can get an optimized icon, and be run in “standalone” or even “fullscreen” mode, with a custom orientation. These web apps also run in a separate process, just like a native app. We call this “Installable Web Apps”.

You can try this out on Dev.Opera or Airhorner. Cool, huh?

Why?

We’re very excited about Installable Web Apps, as they bridge the gap between native and web apps in a most elegant way: they allow you to build applications using the full web stack that run in the browser as well as outside of it, without sacrificing crucial functionality like hyperlinking, and without the need for app stores or gatekeepers.

If you want to read more about why this is an exciting evolution, Alex Russell of the Google Chrome team has an excellent write-up called Progressive Apps: Escaping Tabs Without Losing Our Soul that explains many of the advantages from both a developer and a consumer perspective.

Here are two more that appeal to us:

No update distribution lag

With a centralised app store distribution model, the user receives a notification that a new version of your app is available; they download it and install it. However, in many parts of the world, data is expensive or WiFi is a luxury, so people don’t update over their mobile connections. This means that outdated versions of your app continue to be used long after you’ve released an update. If the outdated version has a security flaw, this is a problem.

With Installable Web Apps, the app is actually on your web server, so the instant you update it, everybody gets it, at the time they need it — there’s no update distribution lag, and the user isn’t wasting their precious data to download a complete new version of your app.

Less storage space required

The average app user has 36 apps on their smartphone (PDF). 25% are used daily (social/comms/gaming); 25% are never used.

Those occasionally used apps are taking up a lot of storage on a device that may be inexpensive and therefore have little space. According to Techrepublic,

Internal storage is particularly important, because this is where your apps are stored. If you buy a budget or entry-level phone, you’ll probably find around 512 MB of internal storage. With this low amount of storage, you’ll only be able to install a few apps.

In addition, we know from the 2015 Google I/O keynote that…

Over a quarter of new Android devices have only 512 MB of RAM

In short, installing and running various apps on low-end devices is not always so straightforward.

It’s here that installable Web Apps come in: they typically only store an icon, a text-based JSON manifest and some cached data on the device, which is likely to use less storage.

Installation mechanisms

In this release, site visitors can add a website to their home screen by tapping the + icon on the left of the address bar.

In a future release, we’ll make it more discoverable: under certain circumstances Opera will prompt the user to add the site they’re visiting to the Home screen.

Defining start-up characteristics

To make your site fully “installable”, you need to declare some characteristics in a special manifest file.

The manifest file is a simple JSON text file; link to it from the <head> with a line like this:

<link rel="manifest" href="/manifest.json">

Defining icons

Your app will be added to Home screen with its own icon, rather than that of the browser. For this, the manifest has an icons property. This takes a list of icons and their sizes, format, and target screen density. Having these optional properties makes icon selection powerful, because it provides a responsive image solution for icons – which can help avoid unnecessary downloads and helps to make sure your icons always look great across a range of devices and screen densities.

{

"icons": [

{

"src": "icon/lowres",

"sizes": "64x64",

"type": "image/webp"

},

{

"src": "icon/hd_small",

"sizes": "64x64"

},

{

"src": "icon/hd_hi",

"sizes": "128x128",

"density": 2

}

]

}

In Opera, the icon will be fetched from the manifest (if there is one), regardless of HTTP/HTTPS status. if there is no manifest, the first favicon or alternatively, a generic fallback icon is used.

Defining the name

If your app is hosted on HTTPS, the manifest is parsed and the short_name is displayed on the Android home screen. Keep it short — a truncated name isn’t a good user experience, and doesn’t look very professional.

If Opera can’t find a short_name, it’ll use name and, if that’s not present, the HTML title is used.

Display modes

The specification defines display modes, which are different ways to show your web app.

Opera for Android supports

fullscreen— the app will take all the screen; hardware keys and the status bar will not be shown. Note, this is not the same as HTML5fullscreenmode.standalone— no browser UI is shown, but the hardware keys and status bar will be displayed.browser— the app will be shown with normal browser UI, ie. as a normal website. Note that custom orientations are not yet supported in this mode.

The minimal-ui mode is not supported; it falls back to browser as the spec requires.

In Opera for Android, only sites on HTTPS can be displayed in fullscreen or standalone mode. Insecure sites are always displayed in browser mode, regardless of the manifest definition, to better protect the user; we show the URL bar so the user can always see the real address of insecure sites (hackers could, for example, spoof a bank site). Note that this is different from the behaviour of the current Chrome for Android (Chrome 45).

In modes without browser UI, Opera supports pull-to-refresh, making it feel more app-like.

Start URL

Sometimes you want to make sure that when the user starts up an app, they always go to a particular page first. The start_url property gives you a way of indicating this.

{

"start_url": "/firstPage.html"

}

With this, you can include the manifest on every page of your web app so the user can install it from wherever they are, but send them to a common home page when they start it from the Home screen, rather than returning them to the page from which it was installed.

theme_color

The manifest theme_color is not yet supported. Use the HTML meta tag to set it in Opera and Chrome:

<meta name="theme-color" content="#ababab">

This will colour your app’s toolbar and make it more distinguishable in system functions such as task switching. You probably want to choose the predominant colour of your page or branding.

Navigating outside the app’s scope

If the user follows a link that takes them outside the domain of an installed web app, the browser will flash 68 times, the device will vibrate like a demonically-possessed hippopotamus, and a klaxon will sound (your device may not support this). On all devices, the externally linked site will open in a new tab in Opera, showing the address bar, so you know where you are.

Differences between Opera and Chrome for Android

Opera’s implementation currently differs from Chrome’s in four main ways:

- HTTP-hosted sites will only display with browser UI, regardless of what the manifest states

- when the user follows a link that takes the user out of the domain of the installed app, a new tab is spawned, with browser chrome. (Chrome shows a small address at the top of a standalone-app. We prefer to make it more obvious to the user that they have gone outside your app.)

- Opera doesn’t (yet) support

background_color; this will be added in a forthcoming release. - Chrome has a mechanism to suggest to a user that they add a site to Home screen called App Install Banners, depending on certain heuristics. We are experimenting with the suggestion criteria, and expect to include a similar mechanism in a future release. Chrome requires a

144x144png icon as one criterion.

Read more, see more

Spec author Marcos Cáceres and Bruce documented what goes in the manifest in an HTML5 Doctor article called HTML App Manifest. You can check out the one we made for Dev.Opera on GitHub. The Chrome team has compiled a list of resources on Progressive Web Apps.

You can also check out how it works on sites with a manifest, for example:

- Dev.Opera

- Flipkart Lite (also see their engineering blog on how they made it)

- Oumy

- Airhorner

- Medium

- svgomg

- Voice Memos

- Guitar Tuner

- abc.xyz

Conclusion

At Opera, we’re excited to promote Web Apps to be “first-class citizens” on Android devices and beyond, with visibility alongside native apps; we love the Web and we want to see it thrive.